A consistent theme at the Australian Festival of Travel Writing was, surprisingly, about how rapidly the world has changed and how this has affected the way we travel through it. I think that many Australians are big travellers as we are not a nation of fast-speed trains, huge public wide-screen televisions or even decent internet connections. We do not boast beautiful old temples or traces of ancient feuds. Both the old and the new astonish us, because we are somewhere in between. In a lot of countries, due to the brevity of time in which a modern lifestyle has been introduced, both can now be simultaneously experienced. You can get a canned hot tea out of a vending machine at the top of a remote mountain in Japan, you can take a ‘selfie’ on your cheaply purchased SLR in an ancient roman aqueduct and you can navigate your way to the Vatican purely based on game maps in Assassins Creed.

Of course, the beauty of these places is timeless, so what makes travelling in a modern age any different? Couturing discuss.

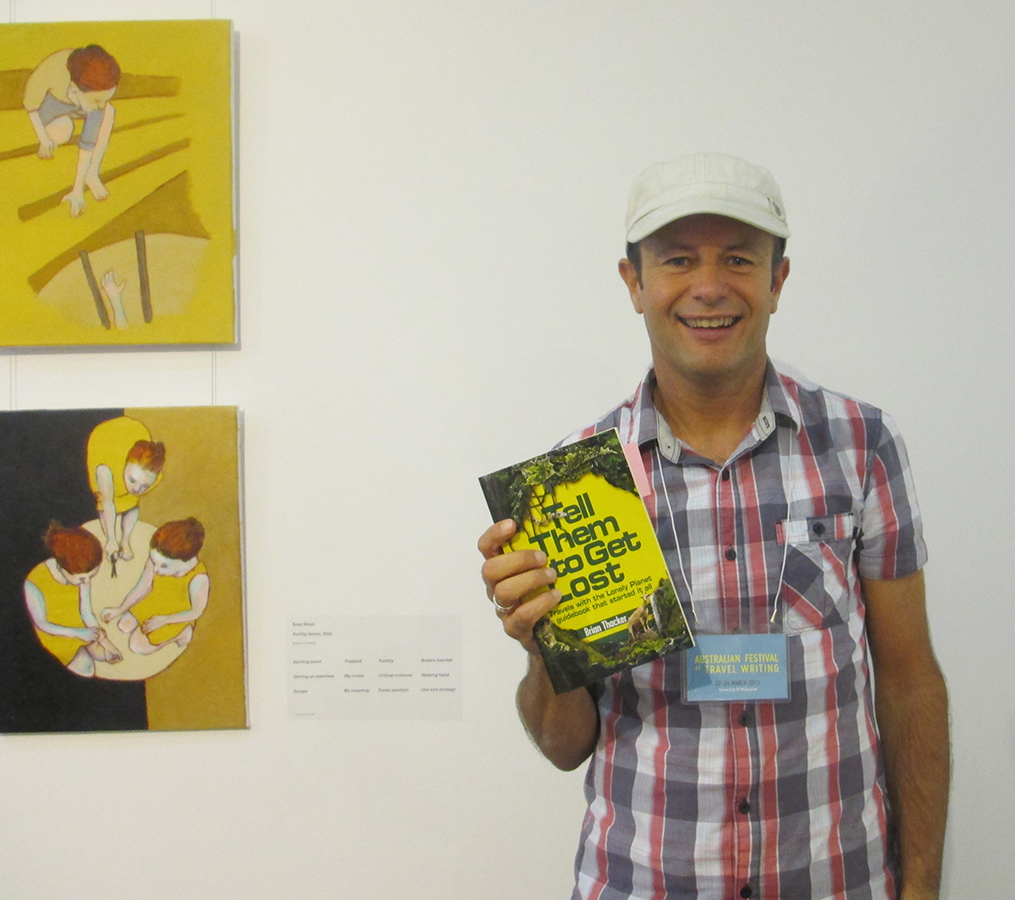

Brian Thacker wrote a book in which he revisited all the locations listed in the very first Lonely Planet guide. Thacker took us back to 1974 with the story of how founders, Tony and Maureen, met on a park bench in London and were married a year later. After wild journeys together they returned to Sydney with 27 cents to their name. They found themselves continually being asked how they managed to live such a lifestyle and go so many amazing places with next to no money, so, they wrote a book about it. You might imagine a very entrepreneurial young couple approaching publishers in suits, but no. They made sketchy hand drawn maps and lists while on-the-go, wrote down all they could read and remember, with very little English signs available to them. Most maps did not have street names jotted down, one key was simply divided into ‘bad roads’ and ‘worse roads’.

Their early seventies novel, glued together and photocopied several times, was Thacker’s only point of reference for his own trip, conducted four decades later. He used their recommendations on where to get the best fruit salad in South East Asia, the best cheap place to stay in Timor and how to find unique architecture in Burma, which was the only place he believed had became more dire since the original book was written. In 2009, he found it interesting what had naturally changed, which buildings and businesses had been turned into MacDonalds, which elements had not changed at all and what had been influenced purely by being listed in Lonely Planet so long ago.

“Lonely planet can actually change a place,” says Thacker. “In Jakarta there’s a guest house, which was listed in the original guidebook, they’d discovered it in the middle of no-where. When the guy opened it everyone on the strip told him he was crazy, that no tourists would come. Once he got in Lonely planet he had to buy the place next door and expand the business, then he had to buy the place next to that… now that street is the resident backpackers street.”

His final destination was the same hotel room (well, it had been split in two, so half of the same hotel room) that the couple compiled their cut and paste novel in. Thacker transcribed his notes and wrote his own novel on possibly the same table. He reflected: “When I was writing those notes, it was so gratifying to see that things are still there and even though the way travel has changed, really, the actual travel side hadn’t. I was still meeting up with backpackers and getting drunk, there were still presentations to gods on the street and people walking to the temple with offerings on their heads. Culturally it hasn’t changed, the same place has still got the best fruit salad, and it’s great to go back.”

Patrick Holland and Maya Ward found that while there is a world that hasn’t changed, travel-writers are always searching for it, searching for ‘authentic experiences’ and that search itself is slightly superficial and hyper modern. In-between ‘authentic experiences’ of people whipping out a traditional dance for possible loose change, travel writers sit in transit lounges, on trains and buses, so Holland wrote about that instead. His novel Riding the Trains in Japan is a series of essays about people that he has met while staying in hotels, things he has observed on public transport, which are uniquely part of a modern culture.

Ward’s novel The Comfort of Water: A River Pilgrimage is about her experience walking the length of the Yarra, starting from Williamstown. “I have traveled all over the world but it was the most stunning adventure I’d ever been on,” says Ward. “Walking out my door with a backpack and going up the Yarra was the happiest, deepest experience of my life.”

The public and private access to a river which for thousands of years has been a shared asset of communities, is something Ward feels deeply passionate about. A feeling by the end of these two lectures was that it is the basic elements of a landscape and culture which transcend the time in which you travel to them. Although the Yarra is now quite polluted in parts and still untouched in others, Ward felt a connection to the river’s history, thus the byline of her novel. Holland likes observing people and their habits, whether it be in a boring bus stop or a beautiful waterfall, human nature is fascinating. And for Thacker, backpacking is bliss. It always has been.

The tip for travel writing, perhaps, is to not just be in awe of new and old culture but also at what is great regardless of time. Like fruit salad.

Leave a Reply